Julia Verena Lalande – Managing Director – Making the Shift – Youth Homelessness Social Innovation Lab

David French – Director of Policy and Planning – A Way Home Canada

For the past year we have been working on Duty to Assist, exploring the Welsh model and co-designing a prototype in Hamilton, ON, to explore how it could be adapted to the Canadian context. But what would it actually take to make Duty to Assist a reality in Canada? When the Canadian Coalition for the Rights of the Child approached us and asked if we wanted to make a submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, we knew that outlining how Duty to Assist could accelerate Canada’s Obligations Under General Comment No. 21 (2017) was the only direction the submission could take. The report is now available, and we want to share our highlights with you.

What are General Comments?

General Comments are published by United Nations treaty bodies to interpret and provide guidance on human rights treaties. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child is the key piece of international law on children’s rights. It describes what children need to survive, grow and reach their potential in life. In 2017, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child published General Comment No. 21 on Children in Street Situations. For the first time ever, street children became the focus of authoritative United Nations guidance to States on how to uphold the rights enshrined in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN CRC). The objectives of the general comment are:

- To clarify the obligations of States in applying a child rights approach to strategies and initiatives for children in street situations;

- To provide comprehensive and authoritative guidance to States on using a holistic, child rights approach to prevent children experiencing rights violations that can result in them having to depend on the streets for their survival; and to promote and protect the rights of children already in street situations;

- To identify the implications of particular articles of the Convention for children in street situations to enhance respect for them as rights holders and full citizens, and to enhance understanding of children’s connections to the street.1

Importantly for Canada and A Way Home Canada, the general comment focus aligns well with the Youth Rights! Right Now Human Rights Guide to Ending Youth Homelessness (the Guide) that was developed in partnership with Canada Without Poverty, the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness and FEANTSA (the European Federation of National Organisations working with the Homeless) under the expertise and guidance of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, Ms. Leilani Farha. The Guide underpins all of our collective work and serves as the foundation for our policy, planning, practice and innovation efforts.

What is Duty to Assist?

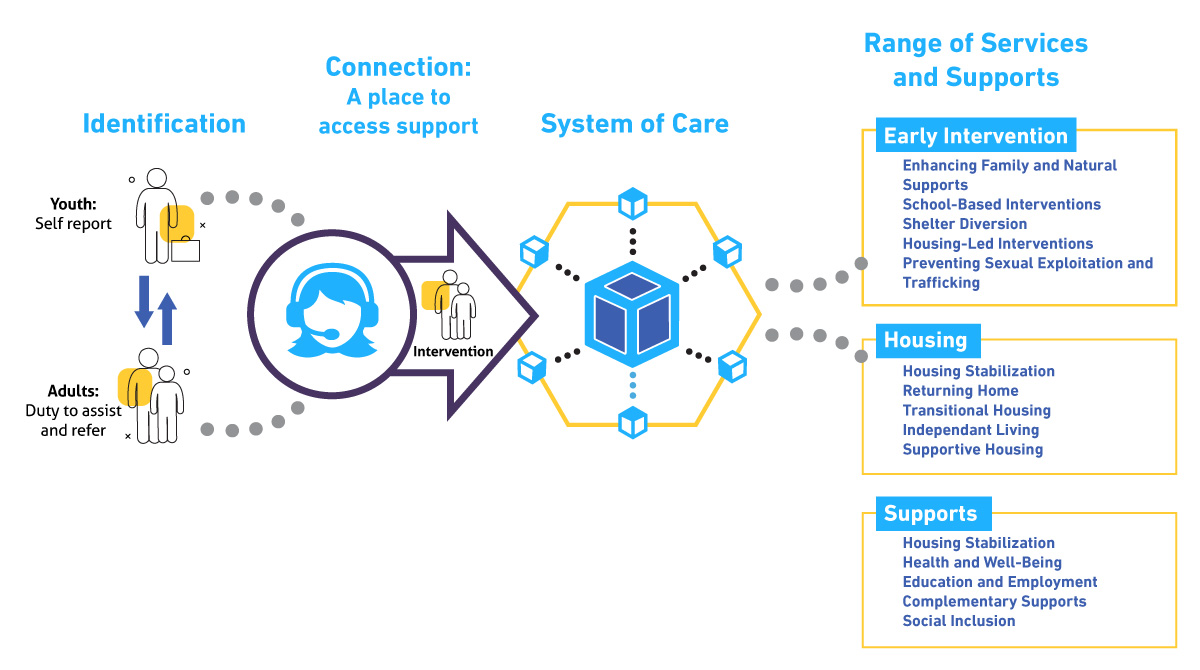

As a rights-based approach to youth homelessness, Duty to Assist legislation identifies and articulates jurisdictional responsibilities within and between different orders of government in order to make their best effort to ensure any young person who is referred for assistance (including through self-referral) is provided with the appropriate supports, information, and advice to remain housed, or quickly become re-housed. This statutory duty is not met by simply referring a young person to an emergency shelter or other homelessness services that do not proactively prevent their homelessness or help them exit homelessness rapidly and in a sustained way. The visual below highlights how Duty to Assist can work in practice:

The Vision for Canada

We have learned so much from our prototype in Hamilton, for example about potential points of intervention, the role that schools might play and resources that front-line staff might need to meaningfully address youth homelessness prevention. This recent blog post dives deeper into what we have learned and how we might be able to apply it. From our initial learning path we know that implementing Duty to Assist will require an investment of resources, cross ministerial responsibility and mandate, and potentially several years of systems work at the community level to ensure prevention-focused systems to support young people are fully in place and well-functioning before Duty to Assist becomes a requirement. It will take combined effort and commitment to make this vision a reality, and even more importantly, a clear roadmap of how to get there.

Our Recommendations for the Way Forward

As part of this work, articulations of clear responsibilities at the federal, provincial/territorial, and municipal levels are critical. Creating alignment across different departments and levels of government is not an easy task, and we realize that it will take some time. Therefore we have crafted five recommendations at the core of this submission that show a clear pathway to implementing Duty to Assist in Canada:

Year 1

- In partnership with the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, the Government of Canada to make a long-term commitment to enshrine the Duty to Assist principles to uphold Canada’s obligations under General Comment 21.

- The Government of Canada to play a leadership role in convening and creating the conditions with provincial, territorial, and Indigenous governments, to explore how Duty to Assist legislation could be implemented.

Years 2, 3 & 4

- The Government of Canada to identify and fund a backbone organization to oversee the implementation of the Duty to Assist principles to ensure their full potential is realized.

- Within Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy, the Government of Canada to invest in five three-year demonstration projects in four provinces or territories to build the evidence base for Duty to Assist nationally.

- These investments can be bundled under the Innovation stream to report on practice methods that can achieve new mandatory level outcomes at the community level of reductions in new inflows into homelessness (note: this is primary and secondary prevention); and returns to homelessness (tertiary prevention).

Years 5

- The Government of Canada to introduce Duty to Assist legislation that identifies and articulates jurisdictional responsibilities within and between different orders of government.

Why is it important?

The submission carries with it an opportunity for governments at all levels to demonstrate their commitment to the most vulnerable young people in Canada. Their responsibility in preventing youth homelessness should carry with it a requirement that young people be assured of a process to gain immediate access to housing and supports to remedy the risk or experience of homelessness. The Duty to Assist legislation signals a shift in policy direction on homelessness from a considerable investment in the crisis response, to one that prioritizes the prevention of homelessness and reorienting systems, services, and funding to accomplish this end.

A Way Home Canada, the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness through our Making the Shift Youth Homelessness Social Innovation Lab are working together to promote effective solutions to youth homelessness that focus on prevention and sustainable exits from homelessness. We want to work with all levels of government, community organizations and service providers to ensure that Duty to Assist can become a reality in Canada.

We highly encourage you to share the submission with local leaders, decision makers, government partners and elected officials at all levels. It is time to accelerate our collective commitments under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and General Comment 21!

1 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Committee on the Rights of the Child General comment No.21 (2017) on children in street situations. June 21, 2017.

https://www.streetchildren.org/resources/general-comment-no-21-2017-on-children-in-street-situations/